- Home

- Reginald Lewis

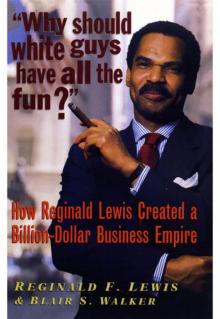

Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?

Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun? Read online

“Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?”

How Reginald Lewis Created a Billion-Dollar Business Empire

“Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?”

How Reginald Lewis Created a Billion-Dollar Business Empire

Reginald F. Lewis and

Blair S. Walker

Black Classic Press

Baltimore

“Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?”

Copyright 1995

Loida Nicolas Lewis and Blair S. Walker

Published 2005

by Black Classic Press

All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2005926148

13 Digit ISBN 978-1-57478-036-9

This special edition was printed by BCP Digital Printing, Inc. to commemorate the opening of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture.

BCP Digital Printing, Inc. is an affiliate company of Black Classic Press

Founded in 1978, Black Classic Press specializes in bringing to light obscure and significant works by and about people of African descent. If our books are not available in your area, ask your local bookseller to order them.

You can obtain a list of our current titles from:

Black Classic Press

c/o List

P.O. Box 13414

Baltimore, MD 21203

Also visit:

www.blackclassic.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of Reginald F. Lewis, my husband, lover, counselor, best friend, role model, and devoted father to our children, Leslie Lourdes and Christina Savilla. It is also dedicated to Carolyn E. Cooper Lewis Fugett, Reginald Lewis’s mother, whose fortitude and wisdom strengthen us all.

—LOIDA NICOLAS LEWIS

This book is dedicated to my daughters, Blair and Bria. May the two of you grow up in a world where accomplished African-American entrepreneurs are the rule, rather than the exception.

It is also dedicated to my wife, Felicia, and to my parents, Dolores Pierre and James Walker: I owe the two of you a debt of gratitude for cultivating in me a respect for—and love of—the written word.

—BLAIR S. WALKER

* * *

Publisher’s Note

“Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?” was the title of a partial autobiography written by Reginald F. Lewis shortly before his death in January 1993. His words are compelling and provide insight into the success he achieved and the personality and intellect that facilitated that success. Blair S. Walker used Lewis’s autobiography as a guide to write a complete biography, based on hundreds of interviews Walker conducted with Lewis’s family, friends, colleagues, business partners, associates, and employees. This unique book includes Reginald Lewis’s own words, here set in italic type, and Blair Walker’s account, which together tell the full story of how Reginald Lewis built a billion-dollar business empire.

* * *

Acknowledgments

I approached this project with a vague sense of trepidation, knowing it would require collaboration with Reginald Lewis’s wife, Loida Lewis. Was she after a full and frank accounting of her late husband’s life, or did she have a lengthy Valentine in mind? Would her involvement lead to a manuscript bearing little relation to reality?

I needn’t have fretted. Loida Lewis proved to be a facilitator of the first order. Her candor and forthrightness were invaluable, as were the insights that only a spouse could provide about someone as intensely private as Reginald Lewis. Whether accompanying me to the Paris restaurant that she and her husband adored, or providing access to Reginald Lewis’s school grades, Loida Lewis consistently strove to make this book as complete as possible, in lieu of Reginald Lewis penning it himself.

The other woman who played an instrumental role in bringing this book to fruition was Ruth Mills, my editor. Every first-time author should be so fortunate as to have Ruth walk them through the intricacies of book writing.

Someone whose thoughts move at the speed of light, and talks nearly as fast, Ruth is a walking clearinghouse when it comes to suggestions and ideas for sharpening prose. She was consistently upbeat and encouraging throughout this project and juggled the roles of editor, psychologist, and confidante with panache.

Another individual deserving of special mention is Rene (Butch) Meily, the spokesman for TLC Beatrice International Foods. From a business standpoint, no one spent more time with Reginald Lewis than Butch. Butch traveled frequently with Reginald Lewis and the two of them spent countless hours hatching strategies for dealing with the press.

Butch went over the manuscript with an eye toward ensuring that events were accurate. Butch was also helpful when it came to defining some of the nuances of his late boss’s personality.

—BLAIR S. WALKER

* * *

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1 A Kid from East Baltimore

Chapter 2 Lewis’s “Demon Work Ethic”: The High School Years

Chapter 3 “I’m Going to Be a Millionaire”: Lewis at Virginia State

Chapter 4 No Application Needed: Breaking Down the Doors of Harvard Law

Chapter 5 Building His Own Law Practice: The Years of Struggle

Chapter 6 “Masterful” Man: Winning Loida Nicolas

Chapter 7 “I Was Not Ready”

Chapter 8 Drexel, the Bear, and the $18 Million Race: Closing the McCall Pattern Deal

Chapter 9 Piloting McCall for a 90-to-1 Gain

Chapter 10 The Biggest Deal of All: The Billion-Dollar LBO of Beatrice

Chapter 11 International Headaches and Domestic Roadblocks

Chapter 12 Bravura and Brinksmanship: Closing the Beatrice Acquisition

Chapter 13 Taming a Business Behemoth

Chapter 14 A Door to a New Universe

Chapter 15 Connoisseur, Philanthropist, Citizen of the World

Chapter 16 “I Am Not Afraid of Death”

Epilogue

Sources Interviewed

Index

* * *

Prologue

Strolling briskly along one of Manhattan’s better known boulevards, 44-year-old Reginald Francis Lewis reared back and unleashed a quick right uppercut. A crisply executed left jab followed, but both punches struck only air, leaving eddies of August humidity in their wake.

Continuing down the Avenue of the Americas in his $2,000, dark blue Italian-made suit, his ruggedly handsome features tinged orange from the mercury street lights, Lewis threw punch after exuberant punch until he grew arm weary. All the while, he flashed a gap-tooth grin and emitted a booming belly laugh as a phalanx of well-dressed business partners accompanying him chuckled too, or looked on with bemused expressions.

Trailing about 50 feet behind with its parking lights on, Lewis’s black Mercedes limousine shadowed the group. Inside the car, where the air conditioner was set at precisely 70 degrees and classical music played on the radio—per Lewis’s instructions—the driver watched attentively for a casual wave of the hand indicating Lewis was tired of walking and ready to ride.

But on the night of August 6, 1987, Reginald Lewis was in the throes of such an invigorating adrenaline rush he could have walked all night and into the dawn. A successful corporate lawyer who remade himself into a financier and buyer of corporations, Lewis had bought the McCall Pattern Co. for $22.5 million, guided it to record earnings and recently sold it for $65 million, fetching a 90-to-1 return on his investment.

But even that improbable achievement was small potatoes compared with what Lewis had pulled off a few hours earlier: This audacious African-American born to a working-class family in Baltimore had just won

the right to buy Beatrice International Foods, a global giant with 64 companies in 31 countries, for just under $1 billion.

That’s why Lewis was happily jabbing his way down the Avenue of the Americas, in a most uncharacteristic public display of mirth and light-heartedness. He and his colleagues had just left the 50th Street offices of investment banker Morgan Stanley, where Lewis signed the papers associated with the Beatrice International auction. Now—foregoing his plush limousine—Lewis preferred to walk the six blocks from 50th Street to the Harvard Club, located at 44th Street.

A richly appointed bastion of Manhattan’s old boy network, the Harvard Club invariably reminded Lewis of just how far he had come from his blue-collar youth in segregated Baltimore and just how far he intended to go.

Constructed of red brick, in the tradition of most of the buildings on Harvard’s campus, the Harvard Club of New York City was a favorite Lewis haunt. He and his victorious entourage walked through the front door and into the lobby, toward the double French doors topped by a sign reading “Members Only.” Lewis half walked, half floated through the double doors, past the over-stuffed couches and desks with Harvard Club stationery on them, and into the Grill Room, with its crimson-colored carpet, walls paneled with dark wood, and subdued lighting.

Lewis seldom went into the cavernous main dining room, where row after row of mounted animal heads grace the walls and chandeliers the size of small plants dangle from the ceiling, above endless rows of tables covered with fresh, white linen.

Passing the Grill Room’s backgammon tables and fireplace, where a fire was usually lit in the wintertime, Lewis walked toward his favorite table. A uniformed waiter with a lilting Caribbean accent rushed up to greet Lewis with a mixture of formality and familiarity established over the course of a long-running relationship.

“Good evening, Mr. Lewis,” the waiter said, smiling.

“How goes it, Archie?” Lewis replied, ebulliently grasping the surprised waiter’s hand and patting him heartily on the back.

Lewis made a move toward his table; then, with surprising fluidness and grace for a man 5-foot-10 and about 20 pounds overweight, changed direction and made a beeline for the snack bar. Sitting on a cantilevered wooden table, as always, was a bowl of popcorn, one filled with pretzels, and another containing Ritz crackers. The fourth bowl had what looked to be a mountain of Cheese Whiz, with two gleaming silver knives sticking in it.

Grabbing a small white porcelain dish embossed with Harvard Club insignia, Lewis filled it with cheese and crackers, then headed to his table, where he ordered two bottles of Cristal champagne—at $120 a pop.

After several toasts, a third bottle of Cristal materialized, followed by a fourth and a fifth, bringing the total to one bottle for each of the five men at Lewis’s table. Lewis cut the celebration short—there was still much work to be done. Winning an auction for Beatrice International was easy compared with the incredibly complex, time-consuming, and expensive effort it would take to close the deal.

Even so, winning the auction was a tremendously satisfying feat, made even sweeter by the fact that Lewis outbid several multinational companies, including Citicorp, that were aided by squads of accountants, lawyers, and financial advisers. Lewis had won by relying on moxie, financial and legal savvy, and the efforts of a two-man team consisting of himself and a recently hired business partner. In fact, when Lewis tendered his bid, a representative of one of the investment banking firms handling the auction called Lewis’s office and said, “We have received from your group an offer to buy Beatrice International for $950 million. We have a small problem—nobody knows who the hell you are!”

The world knew who Lewis was by the time he succumbed to brain cancer in January 1993, at the relatively young age of 50. His net worth was estimated by Forbes at $400 million when he died, putting him on the magazine’s 400 list of wealthiest Americans. In the last five years of his life, Lewis gave away more money than most people dream of earning in several lifetimes, and he generally did so without fanfare.

More than 2,000 people attended Lewis’s funeral and memorial service, including Arthur Ashe, just before his own death. Opera diva Kathleen Battle sang “Amazing Grace” at the memorial service and Lewis’s family received words of condolence from Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan, Colin Powell, and Bill Cosby, among others.

“Regardless of race, color, or creed, we are all dealt a hand to play in this game of life,” Cosby wrote. “And believe me, Reg Lewis played the hell out of his hand!”

With his deep-set, piercing eyes, bushy moustache, seemingly perpetual scowl, and megawatt intensity, Lewis wasn’t the most approachable of individuals. Either through expertise or influence, he commanded respect.

A romantic who once surprised his wife Loida by flying her on his private jet from Paris to Vienna just to hear a classical music concert, Lewis was a Francophile who spoke French fluently and maintained a Paris apartment in King Louis the XIV’s historic Place Du Palais Bourbon. In Manhattan, Lewisesque standards of luxury called for a 15-room, 7-½ bath co-op purchased for $11.5 million from John DeLlorean. Weekend getaways were enjoyed on Long Island in a $4 million Georgian-style mansion.

Charming, irascible, and prone to mood swings, Lewis was as quirky an amalgam of pride, ego, and towering ambition as ever sauntered into a boardroom. Quick to unsheathe his razor-sharp tongue and intellect against adversaries, quaking employees, and even relatives, Lewis achieved one of the more spectacular corporate buyouts in an era of such mega-deals.

But not before he first overcame daunting obstacles and setbacks with a single-mindedness that should inspire not just entrepreneurs but anyone fighting against prohibitive odds, as Lewis did.

Lewis was proud to note that he was the only person ever admitted to Harvard Law School without having so much as submitted an application. But it wasn’t a primrose path that Lewis walked—his acceptance into Harvard Law School came only after he had doggedly maneuvered himself into a position where charm and hard work enabled him to crash the gates.

So it was with most of the noteworthy accomplishments of Lewis’s life. Nothing came easily or without enormous preparation and dedication on his part. A harbinger that Lewis was not one to be cowed or intimidated by barriers of any kind appeared when he was still a small boy.

I remember being in the bathtub, and my grandmother and grandfather were talking about some incident that had been unfair and was racial in nature. They were talking about work and accomplishing things and how racism was getting in the way of that. And they looked at me and said, “Well, maybe it will be different for him.”

I couldn’t have been more than about six years old.

One of them, I can’t remember whether it was my grandfather or my grandmother, said to me, “Well, is it going to be any different for you?”

And as I was climbing out of the tub and they were putting a towel around me, I looked up and said, “Yeah, cause why should white guys have all the fun?”

This is Reginald Lewis’s story.

1

* * *

A Kid from East Baltimore

Reginald Francis Lewis was born on December 7, 1942, in a neighborhood of East Baltimore that he liked to characterize as “semi-tough.” The Baltimore of the 1940s and 1950s was a city of gentility, slow living, and racial segregation. No one had heard of Martin Luther King . . . or civil rights . . . or integration.

As in other Southern cities of the time, there were many things black people in Baltimore couldn’t do. They couldn’t try on clothes or shop at many downtown stores. They couldn’t eat in certain restaurants or go to certain movie theaters.

East Baltimore was a city within a city. It was mostly made up of black migrants from the South who had come North in search of jobs at area steel mills such as Bethlehem Steel at Sparrow’s Point. Lewis grew up in a world marked by block after block of red brick row houses, many of which had outhouses in their backyards. A city ordinance passed in the late 1940s finally outla

wed outdoor toilets.

Tucked deep inside East Baltimore was Dallas Street, where Reginald Lewis spent his early years. More akin to an alley than a street because it was so narrow, Dallas Street was also unpaved. Each house had three or four white marble steps leading directly to the front door. The steps served as porches and outdoor chairs.

Although he didn’t move to Dallas Street until he was five, Lewis would look back on it years later as a special place.

The street was more a collection of rough rocks and pebbles than anything else, unlike the smooth black asphalt of the streets in better neighborhoods. At 7, it didn’t matter that City Hall paved the block just north and just south. That just gave the grown-ups something to talk about all the time. . . . 1022 North Dallas Street, the heart of the ghetto of East Baltimore, is the street where all my dreams got started.

Lewis was born to Clinton and Carolyn Cooper Lewis. Reginald was their only child and not long after his birth, Lewis’s young mother took him to her parents’s home in East Baltimore. Samuel and Savilla “Sue” Cooper lived at 1022 Dallas Street, in one of the ubiquitous brick row houses.

Carolyn’s 6-year-old brother, James, gleefully awaited the arrival of his first nephew. “I can remember the day, the evening—it was starting to get dark—when they brought him home. My sister told me to go upstairs and sit down because I was real fidgety.”

James did as he was told and a moment later, Carolyn appeared holding Reginald. “She handed him to me that day and said, ‘This is your little brother.’ See, I was the little brother and I didn’t like being the little brother. That stood out in my mind, because I am no longer the little brother. I am now the big brother.”

Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?

Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?